Allegations rock Chinese CS2: whistleblower links ex-pro “somebody” a nd cousin “Mr. C” to organized match-fixing ring; BOROS says he was approached to throw a match

Allegations rock Chinese CS2: whistleblower links ex-pro “somebody” and cousin “Mr. C” to organized match-fixing ring; BOROS says he was approached to throw a match

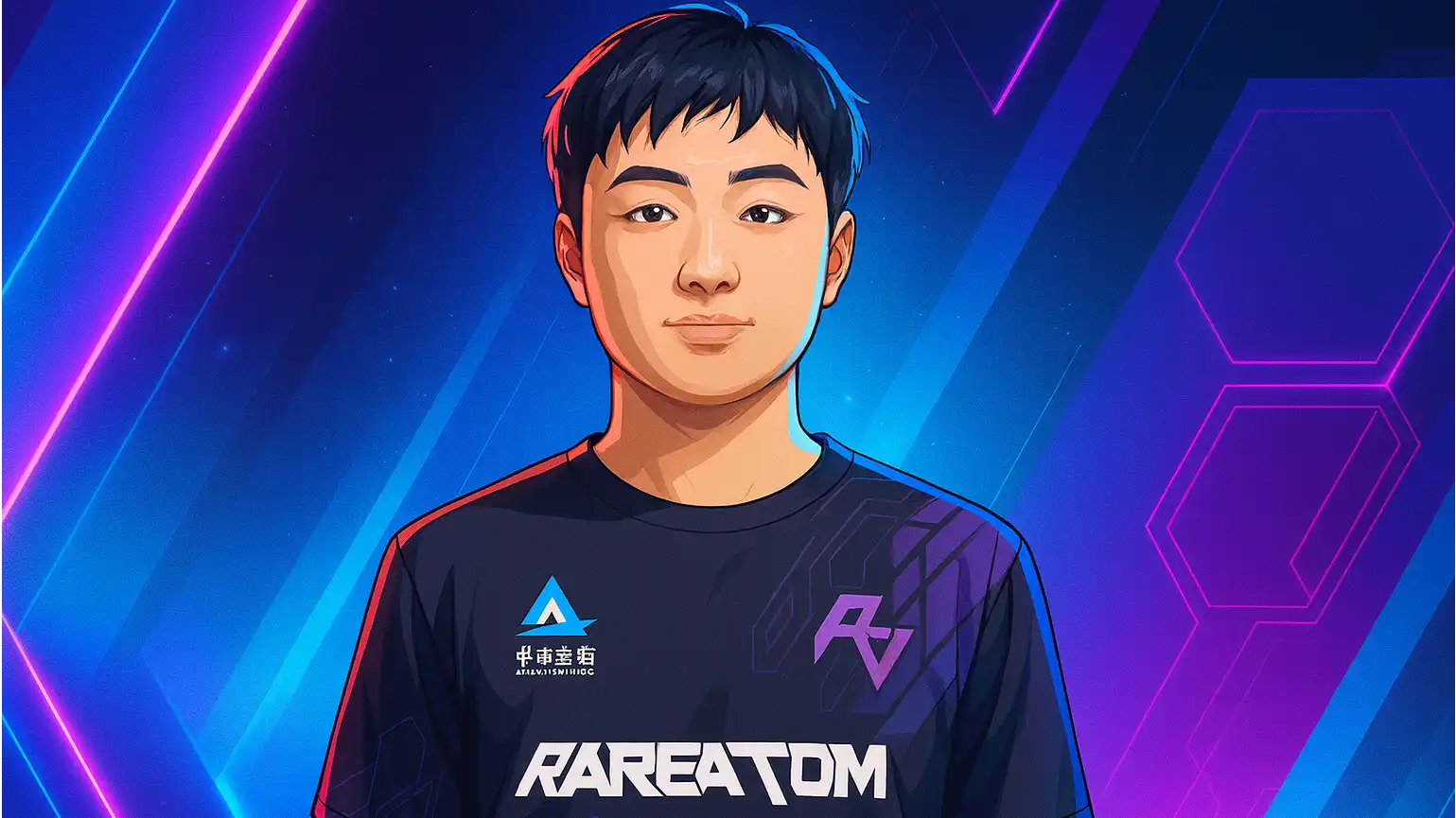

A series of whistleblower posts and player testimonies have triggered one of the most serious integrity scares to hit Chinese Counter-Strike in years, with former TYLOO/Rare Atom rifler Xu “somebody” Haowen and his cousin Chen Peng—known in local circles as “Mr. C”—accused of orchestrating a long-running match-fixing and cheating network. The claims, first amplified by Chinese community figures and mirrored by international outlets, remain under investigation; no official sanctions against the named individuals have been announced as of publication.

What is being alleged

Multiple reports summarize a similar picture: “Mr. C” is described as the organizer of a betting-driven operation, with “somebody” acting as his deputy or “right hand.” The network allegedly influenced results across parts of the Chinese and East-Asian tier-two scene, with accusations extending to the use of hardware-assisted exploits (“soft-router” cheating) to compromise competitive integrity. Several teams are mentioned in community breakdowns as having been affected during different periods; the thrust of the reporting is that players and teams were targets or victims within a system designed to profit from manipulated matches, rather than every named entity being directly complicit.

Community translations and round-ups—based on a Chinese whistleblower stream and subsequent document dumps—outline how the alleged ring functioned: influence over rosters and event participation, bettor coordination, and technical cheating to ensure outcomes. While some sources go as far as calling it the “largest tumour in CN CS2,” none of these claims have yet been tested in an official disciplinary forum.

A pro’s first-hand claim: BOROS says he was asked to fix a match

The story gained international traction when Mohammad “BOROS” Malhas (ex-Falcons/Rare Atom) publicly claimed he had been approached in China to throw a match. In an X post, BOROS tagged @somebodycs, said he refused the approach, and called for action from integrity bodies. His message has since been cited by multiple outlets and sparked further community scrutiny.

Follow-up coverage added that BOROS felt unsafe after rejecting the alleged proposal and sought help to exit the situation—a detail that, if accurate, would elevate the case from betting manipulation to potential player harassment. Again, these statements are publicly posted claims; they have not yet been the subject of a published disciplinary verdict.

What’s confirmed, and what isn’t

-

Confirmed investigations/bans in the region (but not this exact case): Earlier this year, the Esports Integrity Commission (ESIC) issued a range of suspensions—some lengthy—against players and staff from ATOX following a separate match-fixing investigation. Those decisions show that structured integrity probes are active in the region, though they are not the same as the current whistleblower allegations around “somebody/Mr. C.”

-

Unconfirmed at the time of writing: No public ruling or official announcement from Valve, ESIC, or major Chinese tournament operators has directly named or sanctioned the two central figures in this new case. Most of the present material derives from a whistleblower broadcast, community translations, player testimony (BOROS), and secondary reporting.

How the claims spread

The allegations moved quickly through international coverage and social channels:

-

bo3.gg and Strafe summarized the whistleblower narrative, detailing the supposed roles of “Mr. C” and “somebody,” and listing teams said to have been affected.

-

Pley.gg, GGScore/EscoreNews and others highlighted BOROS’s public claim, quoting his X post and subsequent calls for lifetime bans.

-

Community analyses on Reddit compiled timelines, translated snippets, and archived screenshots; separate posts circulated alleged DMs referenced by talent figures, although these are not formal evidence in the disciplinary sense.

Why this matters for CS2

Competitive integrity is foundational for the viability of regional circuits. China’s Counter-Strike scene has rebounded in recent years—TYLOO’s LAN success and the growth of new organisations have expanded opportunities—but sustained suspicion can chill sponsors, impact invites, and discourage international scrims or transfers. Even unproven allegations can produce “soft isolation,” as teams weigh reputational risk.

There is also a technical dimension. Reports of soft-router-based exploits—if validated—suggest an arms race beyond standard anti-cheat, crossing into network-layer manipulation. That raises the bar for TOs (tournament organisers) on venue networking controls, device checks, and data forensics, especially in open qualifiers and tier-two events where on-site resources are thinner.

What could happen next

-

Formal investigations: ESIC and regional TOs have the remit to request data, interview witnesses, and publish rulings. Precedent exists (e.g., the ATOX case) for significant suspensions if evidence meets the standard.

-

Interim actions by teams/TOs: Organisations sometimes bench players pending review, and TOs can enact provisional measures (eligibility holds) if they believe competitive integrity is at risk. There have been no such public actions announced in this case so far.

-

Legal exposure: If betting markets and cross-border payments are involved, local authorities may take interest. That pathway typically moves slower than esports rulings and often remains out of public view until charges are filed.

The bottom line

Right now, the Chinese CS2 match-fixing story sits at the intersection of serious allegations and limited official adjudication. The most concrete, on-record element is BOROS’s first-hand claim that he was approached to fix a match—amplified by reputable esports outlets—and the existence of recent ESIC bans in the same wider region, demonstrating that enforcement mechanisms do operate when cases are substantiated. Everything else remains in the realm of whistleblower description and community evidence that may yet be corroborated—or disproved—by formal investigations.

Until regulators speak, these accusations should be treated as allegations. If and when a governing body publishes findings, we’ll learn whether the names and methods now circulating in public are supported by hard evidence, and how deep the damage runs for Chinese Counter-Strike.