Looking Up at the "Major" From the Outside

Looking Up at the Major From the Outside

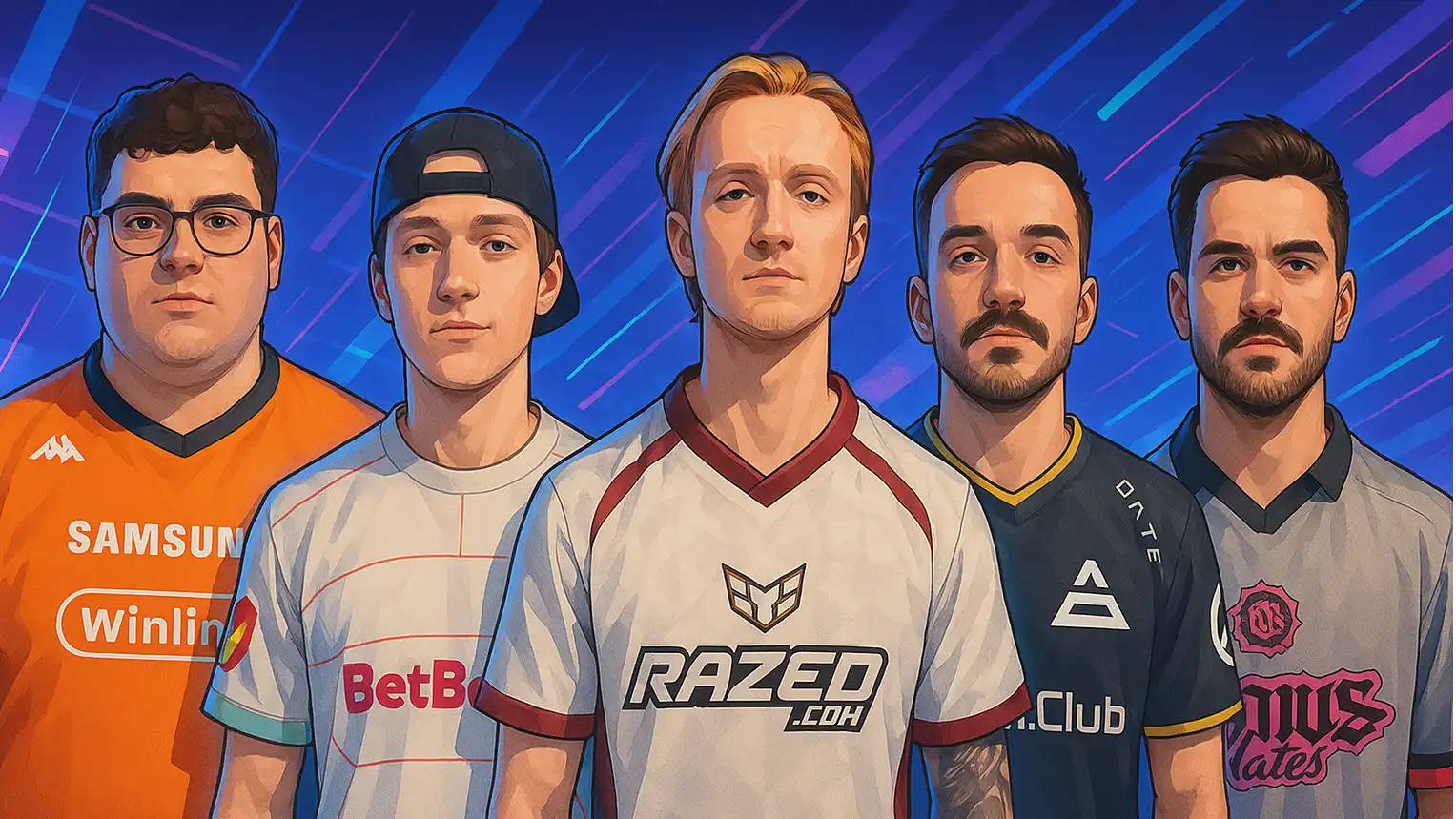

As the 32 teams heading to the StarLadder Budapest Major prepare for the biggest event of the CS2 season, another group stands just outside the spotlight — those who came agonizingly close but fell short under Valve’s new Regional Standings (VRS) system. HLTV spoke with Alejandro “alex” Masanet (Gentle Mates), Christopher “MUTiRiS” Fernandes (SAW), Linus “LNZ” Holtäng (HEROIC), Artem “ArtFr0st” Kharitonov (BetBoom), and Ilya “Perfecto” Zalutskiy (Virtus.pro) about what it feels like to be on the wrong side of the invite line — and just how fair this new qualification landscape really is.

“We Only Have Ourselves to Blame”

For many of the players who missed out, the first reaction wasn’t to criticize Valve or tournament organizers, but to look inward.

SAW were one of the most dramatic victims of the European VRS race. Entering Fragadelphia Blocktober in a strong position, they were knocked out in the quarter-finals by 9INE, allowing fnatic to slide into the last European Major slot.

MUTiRiS didn’t sugarcoat the outcome: “We need to blame ourselves, it was bad from us.” He compared the pressure at Fragadelphia to the old RMR atmosphere, where a single bad result could erase an entire season’s work. At the same time, he pointed to the disadvantages of “local LAN” conditions lacking proper practice rooms or professional facilities.

HEROIC’s LNZ shared similar reflections. Spending most of their season on tier-one LANs, the team played fewer smaller VRS-eligible events. In hindsight, he believes there was still a path to Budapest if they had committed to more lower-tier LANs, but ultimately acknowledged that winning more of the matches they did play would have made the difference.

Gentle Mates, led by alex, mounted one of the most exciting late-season pushes for qualification but ultimately fell short. Alex said the team had real chances but “lost the opportunity” in too many key matches — though he remained proud of their fight throughout the season.

Across the board, players agreed: while the VRS system has its flaws, their missed chances were still decided on the server.

LANs Are Back in Fashion — and That Part Rocks

One undeniable positive of the VRS era has been the surge of mid-tier LANs. With points heavily weighted toward offline results, tournament calendars filled with new and revived events across Europe and North America — from Fragadelphia Blocktober to regionally focused LANs that once held little significance.

Alex, MUTiRiS, and LNZ all praised this shift, highlighting that VRS has pushed CS2 back toward its roots: travel, crowds, and LAN pressure, rather than online grinding.

Veteran coach Luis “peacemaker” Tadeu echoed this sentiment, calling stability the biggest reward of the new system. Instead of a single lucky qualifier, teams must prove themselves across months. He emphasized that “smaller LANs suddenly became valuable again”, turning once-local events into global storylines.

The Grind — and the Loopholes

But the explosion of LANs also comes at a cost. MUTiRiS described the draining schedule many teams endured: weeks away from home, hopping from event to event to maintain VRS standings. It was a level of travel that left players fatigued before their most important matches.

Beyond physical burnout, players also raised concerns about the loopholes in VRS. Perfecto pointed out that, in theory, a well-funded group could host its own LAN, stack the invite list with weaker teams, and farm points with minimal oversight — something far less feasible in the old Minor and RMR ecosystems, where major qualification events were tightly controlled.

MUTiRiS suggested even more worrying scenarios, such as events offering large prize pools to justify significant VRS value but failing to pay out — with points still counting regardless. While no such incidents have been reported, the fact that players raise the possibility reflects their lack of trust.

Even longtime supporters of the system, like peacemaker, believe that stricter roster rules and clearer event validation processes are needed to maintain integrity.

Not Everyone Plays on the Same Map

A deeper issue persists: not all teams have equal access to VRS-relevant opportunities.

LNZ emphasized a core imbalance — teams grinding tier-three LANs against weaker opponents can sometimes earn more VRS points than squads competing at stacked tier-one events. A team might miss qualification despite fighting the top five in the world, while another advances largely by beating tier-four opposition.

Visa issues created another major bottleneck. Virtus.pro saw their season collapse when three players were turned away at the Swedish border due to insurance issues, forcing them to withdraw from ESL Pro League — a key event for defending their invite position. For Perfecto, missing a Major due to bureaucracy was “very terrible and tilting.”

BetBoom faced similar struggles. ArtFr0st explained that the team often couldn’t secure visas, leaving them to compete mostly online — where points are scarce and volatile. One poor online event could erase weeks of progress, effectively locking them out of a fair race.

Peacemaker later listed BetBoom and Virtus.pro among the biggest disappointments of the VRS season, noting that their struggles were shaped as much by external factors — visas, scheduling, instability — as by in-game results.

What VRS Actually Is — and Why It Feels So Different

Part of the controversy comes from how different VRS is from previous systems. It’s Valve’s official ranking model, awarding points based on prize money, opponent strength, and tournament results over roughly six months — with larger events weighted more heavily. These standings determine invites to each region’s online Major Qualifier and influence seeding at the Major itself.

Under the old RMR system, a team could pull off a miracle run and qualify despite a poor season. Under VRS, qualification happens through months of accumulated results — something many fans and players still find opaque.

HLTV’s broader look at the first VRS season described the race as intense and dramatic, but also “a long way short of perfect”, suggesting Valve still needs to refine the system.

Missing the Magic of the RMRs

When players discussed the old RMRs, the nostalgia was unmistakable. Those events allowed underdogs to “dream to qualify” even after setbacks — and SAW themselves had lived one of those stories, qualifying for PGL Major Copenhagen after starting 0–2 at the Europe RMR.

Alex admitted that despite VRS’s benefits, he preferred the emotional rollercoaster of RMRs. LNZ was even more direct, saying he valued both the classic RMRs and the more recent MRQs over qualifying strictly through points.

For many, the essence of the Major lies in a single, pressure-filled LAN where everything is on the line. VRS spreads that drama across months — but in doing so, it also dilutes it.

Where the Debate Stands Going Into Budapest

Taken together, the perspectives reveal a complex picture:

The Big Wins

More LANs across regions

More structured qualification

Fewer fluke BO3 runs deciding Major spots

The Big Problems

Brutal travel schedules

Potentially exploitable event structures

Unequal access to visas and LANs

Players feeling decisions are made off-server

The Big Loss

The emotional clarity and chaos of RMR qualification

Even supporters like peacemaker agree that VRS needs adjustments — stricter rules, better oversight, and a more balanced calendar that rewards commitment without burning players out.

While Budapest will showcase a Major field built on months of consistency, for alex, MUTiRiS, LNZ, ArtFr0st, Perfecto, and many others, it will also be a reminder of narrow margins, missed opportunities, and a system still striving to offer everyone a fair path to the biggest stage in Counter-Strike.